Bolivia’s long-dominant socialist movement reportedly suffered its worst electoral defeat in two decades on Sunday, as voters—frustrated by shortages, runaway inflation, and years of failed leftist governance—turned sharply toward candidates promising economic stability and renewed ties with the United States.

In a stunning rebuke to the ruling Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, Rodrigo Paz, a centrist senator and son of a former president, won the first round of the presidential election with 32 percent of the vote, according to official figures.

Paz will now face former President Jorge Quiroga, a conservative with a record of pro-market reforms, who secured 27 percent support. The October runoff all but ensures that Bolivia will pivot away from socialism toward a more market-oriented, pro-Western government.

The result represents a dramatic collapse for MAS, which has dominated Bolivia’s politics since Evo Morales first took office in 2006. Morales, once hailed as the country’s first indigenous president and a champion of the poor, allied Bolivia closely with Venezuela, China, Iran, and other U.S. adversaries.

Yet today, he is mired in scandal, accused of statutory rape of a 15-year-old girl, and confined to his coca-growing stronghold in Chapare to avoid arrest. He has denied wrongdoing, calling the case a “judicial war” waged by his former ally, President Luis Arce.

But Bolivians appear to have run out of patience with both men. Inflation hit 24 percent in June—the highest in three decades—while shortages of basic goods such as diesel, cooking oil, sugar, and bread have left families struggling.

Arce, so unpopular that he declined to run, has presided over an economy widely described as mismanaged and unsustainable. His party’s candidate, Eduardo del Castillo, barely registered, with just 3 percent of the vote.

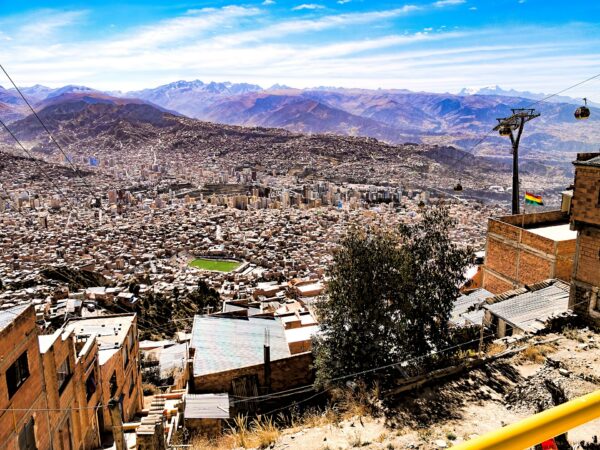

“People have generally stopped believing in Socialism and the left,” said Pachakuti Waranqa, a resident of El Alto, once a stronghold of MAS support. “They want the crisis to end, they want alternatives, they want economic stability.”

Even voters who once backed Morales have turned away. Veronica Mamani, an Aymara resident of El Alto, recalled that Morales initially built infrastructure and expanded social programs. But today she blames him and Arce for soaring prices and shortages. “There are shortages of bread, shortages of sugar and rice. And when you do find them, it’s really expensive,” she said. “Enough with socialism in this country, we need a radical change.”

The economic record explains much of the disillusionment. During Morales’s early years, Bolivia benefited from a boom in natural gas exports, allowing his government to sharply reduce poverty.

But production has fallen nearly in half since 2014, as his administration failed to reinvest in the sector and instead chased a lithium-mining windfall that never arrived. By 2014, central bank reserves had stood at $15 billion; today they hover near $2 billion. The fiscal deficit has ballooned to more than 10 percent of gross domestic product.

“They didn’t take care of the golden goose, they essentially starved it and killed it,” said Eduardo Gamarra, a political scientist at Florida International University.

Markets have responded quickly to the election outcome. Bolivian sovereign bonds have rallied 30 percent this year on investor optimism for a change in leadership.

Economists caution, however, that the next government faces painful choices. “A very harsh adjustment will have to take place,” warned Gonzalo Chávez, an economist at the Catholic University of Bolivia. “That is going to have a big social impact.”

For now, voters appear ready to endure those challenges if it means turning the page on nearly 20 years of failed socialist rule.

[READ MORE: Sudan’s Man-Made Famine Deepens as Global Attention Drifts Elsewhere]